Was Famed Author Peter Matthiessen a Spy or an Informant?

The media avoids untangling the true story behind the man viewed as "one of the great literary libertines of the 20th century."

The post below is from guest contributor Ben Ryder Howe, a journalist and frequent contributor to New York Magazine.

This week sees the publication of TRUE NATURE, a biography of the writer, naturalist, Zen monk and political activist Peter Matthiessen. The 716-page book is expected to be one of fall’s major titles. Matthiessen, who died in 2014, was one of the last literary men of action, known for his sprawling New Yorker travelogues on crossing the Amazon and summiting the Himalayas as well as for his National Book Award-winning fiction.

Matthiessen also spied for the CIA, which his son Lucas accidentally disclosed to a New York Times reporter at a Christmas party for The Paris Review in 1977. The Times subsequently revealed Matthiessen’s secret in an article, “Worldwide Propaganda Network Built by CIA,” which came out in the wake of the Church Committee hearings into intelligence abuses. At the time, the press was aggressively investigating the CIA. Matthiessen, one of the decade’s biggest literary names, was a surprise catch. The revelation threatened his career and trailed him to its end. He called working for the agency “the one adventure of my life I regret.”

Nevertheless, despite being questioned about it dozens of times over the years, he succeeded in never revealing what he had actually done. Was he an agent or a case officer? Did he have a security clearance? Did he handle other sources of intelligence, or was he the one being handled? Who or what was he spying on?

Unfortunately, the new biography doesn’t solve the mystery, or even really try. We should want to know what Matthiessen did, because there have long been unsettling indications that he spied on other writers – particularly dissident writers, including Richard Wright, the towering midcentury author of BLACK BOY, who was hounded into exile by J. Edgar Hoover because of his political activism and died an early death likely because of the stress.

We should also want to know because researchers, including TRUE NATURE’s author, Lance Richardson, have spent decades trying to get the CIA to release Matthiessen’s file, as well as the agency’s files on The Paris Review, which Matthiessen used as cover while spying – all without success. Whatever secrets the files contain, they are now almost seventy-five years old, nearly the same age as the CIA itself, raising the question: will the public ever get to know what they are? Given that nearly everyone involved has died, one has to wonder, Why all the discretion?

The intrigue centers on a few years in postwar Paris, one of the more remarkable periods in American culture. Long a magnet for expat artists, Paris saw its popularity surge after the war as living costs sank and the U.S. oppressed nonconformity at home. It was the age of McCarthyism, blacklists and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Anyone who ventured into politically unacceptable territory risked their careers. Black artists, gay artists, creators of “smut,” as well as those who just wanted a taste of subversive art, great jazz and nostalgia for the Lost Generation, flocked to the Left Bank. Among the unknowns loafing at the Deux Magots and the Tournon were James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Bud Powell, Mary McCarthy, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Joan Mitchell and Ellsworth Kelly.

The scene caught the eye of intelligence agencies. The U.S. was at a disadvantage in the cold war when it came to soft power. Moscow had long excelled at penetrating Western intellectual circles, and Washington was determined to fight back by promoting Western values through literature, Hollywood, music and even abstract expressionist painting. Paris was the epicenter of the international arts scene – soon, much of it fueled by CIA money and flooded with spies.

Peter Matthiessen was one. As TRUE NATURE tells it, Matthiessen arrived in Paris in 1953 fresh out of Yale, where he was one of “at least twenty-five” members of his class (including William F. Buckley, Jr.) recruited by faculty members into the CIA. The young writer – handsome, connected, and fluent in French – was already on his way to fame, having published stories in The Atlantic. The CIA gave him a stipend and a mission he embraced.

“When you’re 23, it seems pretty romantic to go to Paris with yr beautiful young wife to serve as an intelligence agent and write the Great American Novel into the bargain,” Matthiessen would write to his friend Ben Bradlee, Jr, executive editor of the Washington Post. “Weren’t you ever as young and dumb as that?”

It all turned sour, however. Matthiessen’s romantic vision of spying seems to have involved spying on foreigners – Russians, or perhaps European communists. Which he did some of the time. Richardson tells us about his attempts to learn the inner workings of the French communist party from an older writer who he approached pretending to seek feedback on a novel. (Richardson posits that it was Tristan Tzara, a Dadaist poet and art collector.)

For the most part, however, Matthiessen seems to have spied on other expats, which blurs the lines between spying and something less noble: informing. Matthiessen was gathering information on friends, many of whom had legitimate reasons to be petrified of the government at home, which could and often did seek to harm their careers and terrorize their families. While he pretended to be just another slumming postgrad, in reality, as he would later describe, usually between his teeth, his actual duties were “checking on Americans.”

Richard Wright would have been an obvious target. A former member of the Communist Party USA, Wright had published a massive bestseller, NATIVE SON, in 1940, then moved to France to escape blacklisting and surveillance. There, while continuing to denounce the U.S., he mentored a community of black dissident writers, including future FBI target James Baldwin.

It isn’t publicly known whether Matthiessen spied on Wright. After his son unintentionally outed him, Matthiessen’s luck turned in his favor, as the media seemed to lose interest. Although some of his old Paris friends, such as the writer Irwin Shaw, came to him demanding to know whether he had spied on them (denounced as a communist, Shaw had been forced to move abroad) most of his peers seemed to shrug. Indeed, shortly after the Times article, a panel of fellow writers would lavish him with the National Book Award for THE SNOW LEOPARD – twice, in the nonfiction and contemporary thought categories. Whether it was wagon-circling or indifference, Matthiessen seemed to be in the clear. His greatest renown would come after he was exposed.

Had he faced questions about informing on one of the leading anti-racists of the time, it might have been different.

The first journalist to push deeper into the Paris years was Scottish writer James Campbell, who has long written for the Times Literary Supplement. In 1991 Campbell published a biography of Baldwin, TALKING AT THE GATES, for which he succeeded in obtaining Baldwin’s FBI file. For his next book, PARIS INTERZONE, he turned to Wright. Campbell contacted George Plimpton, co-founder with Matthiessen of The Paris Review. Initially he found little resistance. Plimpton freely admitted that a “prominent member” of the review – Matthiessen – had worked for the CIA but quit “after being asked to spy on the expatriate community.” A year after the interview, Campbell sent Plimpton galleys of EXILED IN PARIS, which he hoped the review might excerpt. Instead, Plimpton threatened to sue him unless he removed the material he had given him. Campbell published most of it anyway. There was nothing particularly inflammatory about it, leaving Campbell confused. One possibility: Plimpton just wanted the spying issue to go away, which it had after the Times exposé. However, the book not only brought it back but raised difficult issues, including Wright’s troubling death by heart attack at age 52, which Campbell believes to have been caused by paranoia and stress but others attributed to intelligence agency malfeasance. (Wright’s daughter and friends believed he had been poisoned.)

TRUE NATURE doesn’t mention Campbell’s work. Although Richardson asks, “Was Matthiessen watching Richard Wright?” he doesn’t say whether he knows the answer. The Matthiessen estate gave him broad access to his papers. In addition, he thanks the Matthiessen family for its “willing cooperation.” Yet there’s an obliqueness that mirrors his subject whenever Matthiessen’s espionage comes up. Overall, “[w]hat Matthiessen did, day to day for the CIA, remains something of a mystery,” he writes. The best he can offer is a 2008 exchange with Charlie Rose in which Rose asked point blank what Matthiessen did for the CIA.

“Well, I think we’ll just have to go to the rest of the show,” Matthiessen responded. “It wasn’t very much. It was pretty paltry, really. What it really was doing . . . Know what I was doing, spending my day doing? Deceiving people. That’s all it is.”

“Deceiving people as to—?”

“As to who you are, your identity, what you’re up to, what you want to know [. . .]”

“Were you looking for people you can convert? Were you looking to expose people?”

“No, I was getting information on people.”

Another author TRUE NATURE curiously neglects is historian Craig Lanier Allen. In 2019 Allen published a dissertation specifically focused on the question of Matthiessen’s spying and whether he was targeting Wright. Allen brought a unique perspective, as a black historian and a former spy himself, having spent decades posted abroad by U.S. Air Force counterintelligence. His thesis, “Spies Spying on Spies Spying: The Gibson Affair, the Café Tournon, and the Specter of Surveillance in Postwar American Literary Expatriate Paris, 1953-1958,” is driven by Allen’s own internal conflict: sympathy, on one hand, for the secret agent, and on the other, for the dissident, truth-seeker and outraged critic of race relations. He calls Wright a security threat whose “complicity warrants investigation.” However, he also makes it clear that Wright was a man of conscience who endured monstrous abuse.

Unlike Richardson, Allen shows real interest in getting to the bottom of Matthiessen’s spying. In one devastating quote, he shows that if he did spy on Wright (which Allen believes he did), it was unquestionably a personal betrayal.

“I was very good friends with Richard Wright who was there in Paris too and we had interesting talks about Baldwin,” Matthiessen told an interviewer in 2001. Allen goes on to analyze the clues scattered among Matthiessen’s decades of shifting statements. As a trained spy himself, he identifies what he calls “repeated patterns of deception consistent with the training of a professional intelligence operative.” Matthiessen, he argues, used “the requisite amount of plausible deniability and purposeful obfuscation” to indicate that he was hiding something.

But again, what? Allen doesn’t quite have the goods either. What he does have is the professional standing to engage in informed speculation. In his opinion, Matthiessen probably didn’t have a significant role in the CIA. He was unlikely to have been a case officer. He probably “did not himself manage other human sources of information,” but rather would have “himself been managed.” He was not, in other words, a salaried employee of what was then a burgeoning American intelligence apparatus. He was probably a contract worker hired for a specific purpose – to infiltrate the expat scene. Which some would see as an informant.

Would the distinction have mattered to someone like Wright, whose FBI file largely consisted of fellow writers and acquaintances informing on him, some for money or privileges? (The privilege of simply crossing borders, which included returning home, was cunningly rationed by the U.S. embassy in Paris.) Wright suspected everyone, especially other writers, and likely suspected Matthiessen, too. Indeed, many expats probably suspected Matthiessen, whose wife at the time was the daughter of a top U.S. diplomat.

In Allen’s view, Wright deserved to be spied on. He was a dissident with a platform, “willing to go to any length in order to attract attention to the problem of racial discrimination,” as one of his informants (not Matthiessen) wrote. That made him a “threat to U.S. national security interests,” says Allen.

Yet his enemy was at home. It wasn’t the State Department or the CIA that was obsessed with him, as Allen points out. (Wright’s file was larger than that of any American writer of his time.) It was the FBI, which is supposed to be a domestic intelligence agency. Wright was being hounded, even abroad, with the help of friends and allies. His treatment was undeniably foul, as Matthiessen, looking back, must have painfully felt. In later years Matthiessen would defend himself by distinguishing the CIA of the 1950s from the somewhat later one that came under the scrutiny of the Church Commission – before the agency “got into assassinations and all the ugly stuff,” he would say. But spying on friends is arguably the essence of an intelligence service – any intelligence service, American or otherwise.

In Matthiessen’s defense, most Americans were still processing the terms of the cold war in the early 1950s, gauging the enemy threat and figuring out just how far the nation should go to defend itself. Matthiessen, “the young Yalie,” as he described himself, drinking martinis at the club, was hardly the only one whispering about acquaintances. “Everybody thought everybody else was informing on someone or other for somebody,” said the poet Christopher Logue. Even Wright was accused of selling information.

According to Richardson, the reason Matthiessen dissembled so much was shame. At the end of his life the spying agonized him, and he made several attempts to expiate himself on paper, including something titled “THE PARIS REVIEW v. THE CIA: My Half-life as a Capitalist Running Dog.” TRUE NATURE gives us glimpses of his anguish. Which unless the CIA changes its mind about releasing Matthiessen’s file, is all we have. Allen tried harder with less, and after publishing his thesis he promised that Matthiessen’s involvement with the CIA would soon be explored “as part of a more expansive research project.” Unfortunately, he died in 2022 at the age of 52 of a heart attack.

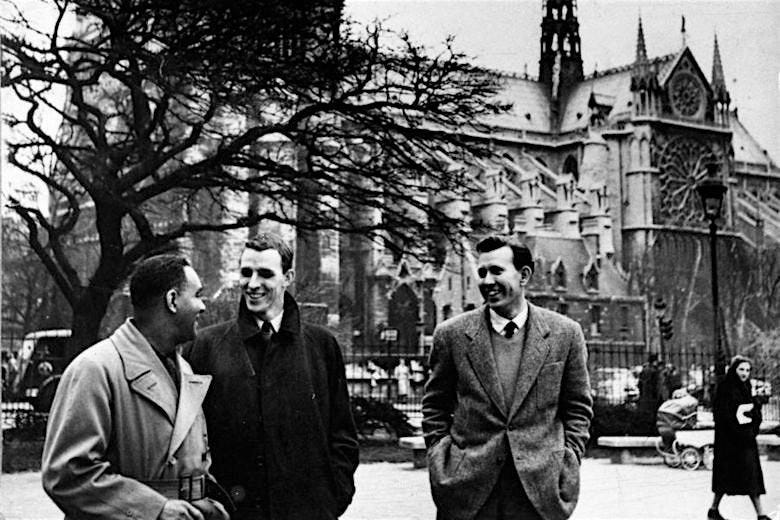

The first photo features Peter Matthiesen posing on the harbor on May 29,1992 in Saint Malo,France. (Ulf Andersen/Getty Images). The second photo shows Richard Wright, Peter Matthiessen and Christopher Logue. Post updated on Oct. 16th to correct the Talking at the Gates publication date, name of James Campbell’s book.

Wow! What an interesting article. I had no idea Wright was abused and was sorry to learn it. I would like to know more about this subject. Thanks Lee.

I can't imagine why the CIA would still be concealing this information -- other than the fact that they can.