Netflix's Disneyfication of Bayard Rustin

The new biopic fails to capture the genius of the famed civil rights strategist and organizer. Instead of exploring his intellect, the film focuses on his gay identity.

One of the most memorable books I read last year was Down the Line, a collection of speeches and writings from political theorist and strategist Bayard Rustin. So I had great anticipation for the Netflix biopic on his life, released last Friday. The movie, created by Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company and directed by George C. Wolfe, was a flop. The film was so disappointing that it compelled me to write my first movie review for this Substack – so if you plan on watching it, there are some spoilers below.

The film is a conscious effort to acknowledge and uplift Rustin, one of the most unsung heroes of the civil rights movement. As an openly gay man living in the mid-twentieth century, Rustin faced immense struggles, both in society and within the civil rights establishment in which he worked. That aspect of his life takes up almost half the film, as a tragic romance with an assistant and with a pastor on the NAACP board sets the narrative backdrop. The rest of the film portrays Rustin, a close advisor to Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., forcefully pushing for and organizing the 1963 March on Washington.

In no clear terms are Rustin’s humanist beliefs, his study of economic and social forces, or his carefully articulated worldview ever depicted on the screen. The film reduces him to a meticulous organizer – focused on how many latrines and buses will be prepared to make the march a success – and an individual sharply persecuted for his sexual orientation.

The process is familiar and not terribly surprising. It’s a distinct Disneyfication applied to biopics that dries out any political figure to render them palatable to a mass audience.

But such a depiction ultimately robs Rustin of any intellectual heft and ignores his pointed objections to the direction that many in the movement were headed. By portraying Rustin simply as a modern avatar of gay identity, the film promotes a form of identity politics that runs counter to his core values. Rustin was an avowed opponent of sectarianism in all of its forms, including black nationalism. Throughout his life, he emphasized humanistic values of equality and believed that “there is no possibility for black people making progress if we emphasize only race.” He opposed affirmative action and mocked black separatists like Stokely Carmichael for charging “$2,500 a lecture for telling white people how they stink.” Rather than dividing society by race, creed, or color, Rustin wanted freedom, equality, and opportunity.

In 1970, writing in Harpers, Rustin pilloried the ascendent black separatist movement, which he believed would set back the goals of social progress:

One is supposed to think black, dress black, eat black and buy black without reference to the question of what such a program actually contributes to advancing the cause of social justice. Since real victories are thought to be unattainable, issues become important in so far as they can provide symbolic victories. Dramatic confrontations are staged which serve as an outlet for radical energy but which in no way further the achievement of radical social goals. […]

Such actions constitute a politics of escape rooted in hopelessness and further reinforced by government inaction. Deracinated liberals may romanticize this politics, nihilistic new leftists may imitate it, but ordinary Negroes will be the victim of its powerlessness to work any genuine change in their condition.

Rustin viewed both the rise of identity-based racial chauvinist movements like the Black Panthers and the Nixononian southern strategy as a threat to the broad working-class coalition that had enacted much of the New Deal and Great Society. The movie abandons his pointed criticisms of the New Left. The only reference to his strongly held ideals are a few scenes in which he defends the principle of nonviolent civil disobedience.

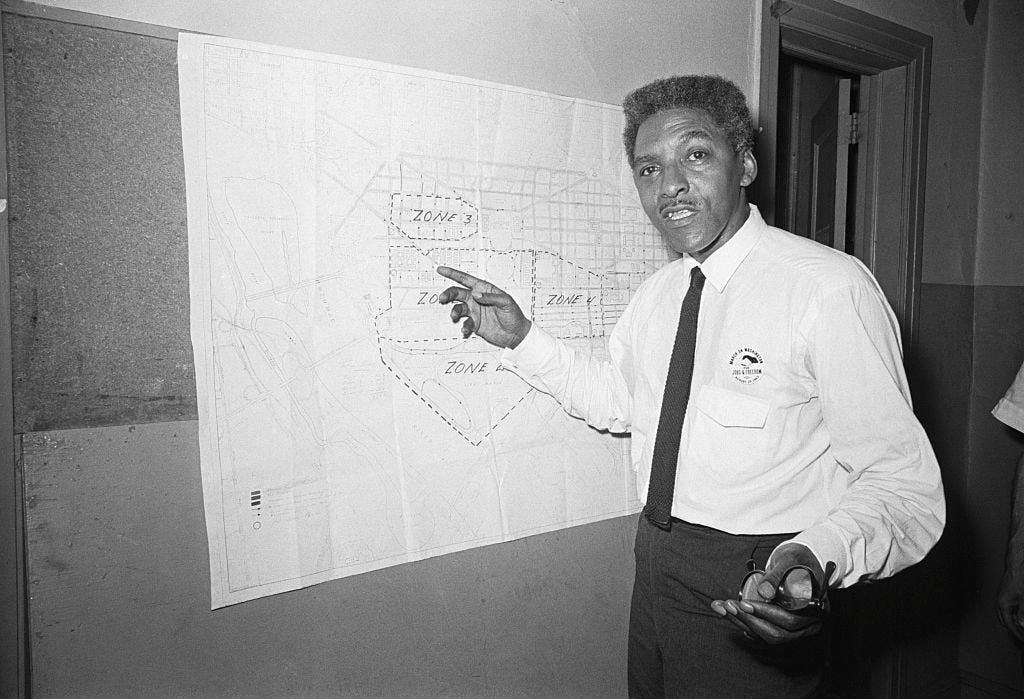

The film also does absolutely nothing to explore Rustin’s economic views, which guided much of his activism and shaped the march that the film revolves around. The only hint of economic concern is raised by his close ties to the famed labor leader A. Philip Randolph, who plays the part of the “trusted friend” archetype with no ideas of his own. Late in the film, placards reveal that the grand demonstration Rustin had pulled together was titled the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” The jobs part appears out of thin air with no explanation. Here’s how Rustin later wrote about how he and Randolph envisioned the march in the pages of the New Leader in 1969:

It was Randolph’s perception of the economic basis of Negro freedom that enabled him to grasp the unique significance of the 1963 March on Washington. He conceived of it as marking the termination of the mass protest period – during which Negores had destroyed the Jim Crow institutions in the south – and the inauguration of an era of massive action at the ballot box designed to bring about new economic programs. Aware that the central problem Negroes faced was no longer simply one of civil rights but of economic rights – for the one would lack social substance without the other – he called for a March on Washington, which brought a quarter of a million Americans to the nation’s capital to demand “Jobs and Freedom.” […]

Randolph was not speaking here of tax incentives for industry, voluntary assistance by private individuals, or community action programs. He was speaking of full employment and a guaranteed income, the building of our cities, the provision of superior schools for all of our children, and free medical care for all our citizens. He was speaking, very simply and without rhetoric, of achieving equality in America.And he was not being unrealistic. He proposed, along with the Freedom Budget, a political strategy for achieving it that calls for building a coalition of Negroes, labor, liberals, religious organizations, and students. If these groups could unite, they would form a majority capable of democraticizing the economic, social and political power of this nation.

Today there are many Negroes and liberals who reject the idea of this coalition. The reason for this, I think, is that they have failed to view the problem of inequality in its totality. Unlike Randolph, their vision is fractured and constricted. Some Negroes, for example, are advocating racial separatism and black nationalism because they are engaged in a very significant psychological quest for identity. […]

Indeed, many liberals have become obsessed with the psycholoigcal aspects of the racial problem to the point of neglecting its economic dimensions. During the early years of the civil rights movement these liberals, unlike Randolph, favored integration primarily as a means of fostering better relations between blacks and whites. Now that the cry of black nationalism has arisen from some Negroes, they have transferred their concern for brotherhood to the need for blacks to achieve pride and identity and for whites to purge themselves of guilt and racism. In both the earlier and the current cases there is a failure to confront the overriding fact of poverty. Most mistakenly, many have now abandoned the objective of building an integrated movement to achieve economic equality.

A closer read on Rustin’s thinking shows that he was deeply concerned that simply eradicating voting restrictions and legal segregation was woefully inadequate. Black Americans, he worried, were facing profound obstacles, including rapid automation in factories that pushed workers out of jobs, urban decay, and de facto school segregation. “These are problems which, while conditioned by Jim Crow, do not vanish upon its demise,” Rustin noted in an essay in Commentary.